9/11

My heart pounded as I walked between the rows of thousands of American flags. I wanted the space to grieve, to take in the sadness and the beauty of the sea of red, white and blue in front of me, but I was constantly on edge of thinking about how surely I didn’t belong there. Surely people were looking and thinking well what is she doing here anyways.

This feeling was not a new one to me. Ask any Muslim-American about growing up in post-9/11 world, and you’ll hear similar threads of shared emotions, of shared experiences between us. Of the dichotomy between their faith and their nationality. Of needing to gravitate towards one or the other, or perhaps rejecting it all. Of “random” airport screenings. Of always being considered suspicious, and being terrified of being blamed for something, anything, going wrong around you. Of looking at the clock and it always being 9:11. Of the fear of saying “that’s the bomb!”. Of the fear of bombings or attacks happening around you, or far from you and having to explain them away. Of years of side-eyes and snide comments and taunting and bullying. Of being too Muslim, of not being American enough. The weight of a generation’s hatred towards our people was not without its effects. Hundreds of thousands of kids were thrust into the position of repudiating events and ideals that had nothing to do with them at all. More than the physical burden, there was a deep emotional toll burned into our collective consciences. It was recently published that American-Muslims were two times more likely than other faith groups to attempt suicide (there’s an amalgamation of reasons for this, of course, but the conversation at hand cannot be denied).

I looked at the flags around me on Art Hill and attempted to process the hundreds of emotions running through me. The 7000+ flags were pitched to pay tribute to the American soldiers who died in battle in the wars that have been waged since 9/11. The inaugural Flags of Valor event was held 10 years ago, where there were 2,977 flags raised, one for each of the lives lost at the Twin Towers, the Pentagon, on Flight 93 and the first responders who gave their lives to save others. It’s a haunting memorial. The American flag, which means home to me and I claim more deeply than any other, is the same flag that momentarily strikes fear into my heart when I see it as I’ve been taught I’m not usually welcome where it flies.

I don’t remember too much from the immediate aftermath of 9/11.

I remember the day clearly, of course, as everyone does.

Tuesday, September 11, 2001 is ingrained in every American’s mind - where you were that day, what you were doing when you first heard the news.

I was in third grade. I walked to my elementary school behind my house as I always did. I saw my friends as we waited in line outside the doors; I put away my backpack and lunch into our cubbies. I recited the Pledge of Allegiance, hand over heart, as we did every day. It was a normal morning, until the second morning announcement came overhead. All I remember is some words about an incident in New York, and that we would have a moment of silence. The rest of the day seemed the same to me, except for a buzz amongst the adults that I didn’t give a second thought to. I remember coming home and turning on the TV, ready to watch my usual after school PBS kids, and all I saw was the same scene over and over and over again, no matter which channel I scrolled to. Death, destruction, despair. Terror. Faces of men with beards and towpees and thaubs, familiar to me in the faces of my parent’s friends and grandparents, being demonized.

I had no idea what any of it meant. How could I? I was only eight. How could I know that the country my parents had immigrated to to give their kids a better future had suddenly turned against their kind?

I don’t remember my parents ever explicitly talking to me about that day.

They were my heroes in that regard. They raised me to be unapologetically Muslim, in a world that didn’t accept them as they were: immigrants, people of color, Muslims in an increasingly Islamophobic world. There are very fuzzy memories of hushed conversations between them, an incident or two that was briefly mentioned about a slur on the train, a thrown drink at a restaurant, but was quickly moved past. Though I know they lived in fear of the retaliation against them, they shielded their children from all of it. My parents didn’t for a second let me believe that there wasn’t anything I could do, or have anything I wanted, that there were any limitations the what I could achieve as a Muslim female in the USA.

It took me a long time to understand that the Islam that I grew up with and was taught at home, in the mosque, at Sunday School, was the same “Islam” practiced by those we were now at war with were supposedly the same. It wasn’t until much later that I was able to verbalize that the so-called Islam being quoted by the ‘terrorists’ was analogous to the KKK and Christianity.

***

I recently watched the “9/11: One Day in America” mini-series on HULU this week, and was amazed by how much I did not know about the day that shaped the rest of my life experiences. I had previously only known that planes were flown into the Twin Towers and that ~3000 lives were lost. I had forgotten about the Pentagon, I hadn’t known at all about Flight 93. I didn’t know the stories of the first responders and their bravery, I didn’t know about the survivors. I cried watching it. I thought back to my visit to Ground Zero several years prior, the beautiful memorial that had been constructed in the place of destruction. Of running my fingers over the names of strangers to me. I thought about it as I stood amongst the sea of flags, and the dog tags clinking in the wind of all the service members who had lost their lives since. I mourned the day and the lives lost and for everything that was to come. More than all of that, I grieved the international effects of this War on Terror, on the impacts of the ‘expansion of American imperialism’, of the 240,000+ Afghans and the 208,000+ Iraqis who have died, and the millions of others who have been displaced, captured, tortured, detained, questioned, harassed. I grieved the loss of childhood and innocence of those here and abroad.

***

The intervening days, months, and years from 9/11 are not clear to me. I remember snippets of the rest of elementary and middle school, focused more on friendships and popularity and crushes on boys and classes and grades and the plights of puberty than on the events of the world around me.

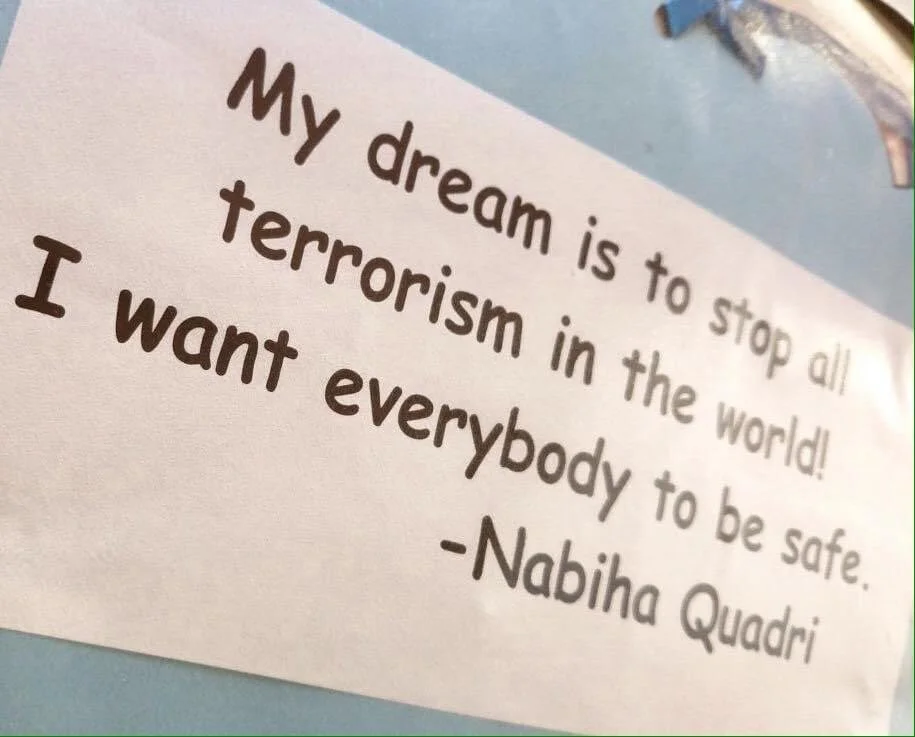

I do remember this one thing: Martin Luther King Day in 2004. It was fifth grade, and our class was instructed to write out our dream for the future, for the quintessential “I Have a Dream” exercise.

“My dream is to stop all the terrorism in the world,” I wrote. “I want everybody to be safe.”

The dreams were printed out and pasted onto clouds that were then hung up from the ceilings. I went through the hallway the next day, and read through them. I saw wishes for fame, for future riches, for Olympic achievements. I saw mine, starkly different in tone from all those around them. I hadn’t understood the assignment, I thought. I was ashamed and embarrassed of it, the clear outlier from all the other dreams of my fellow ten year olds. I stand here twenty years after the events, reflecting on all that’s happened since. My dream, ashamed though I was of it years ago, remains largely the same.

Twenty years have passed since that fateful day, and this is just one person’s experience of how she was deeply affected. I recognize that I certainly am lucky in that I haven’t suffered the way others have, and in spite of everything mentioned above, I lead an incredibly blessed and privileged life. It may have been inherent, or it may have been spurred by the fear of being “less than”, but I have a pathological need to continuously be better, do better. I have been fortunate enough to achieve more than I ever though possible, and hope to continue to do so no matter the sentiment around me.